Southern Railway (U.S.)

| |

A Southern Railway train in 1969 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Key people |

|

| Founders | Charles H. Coster Samuel Spencer Francis Lynde Stetson |

| Reporting mark | SOU |

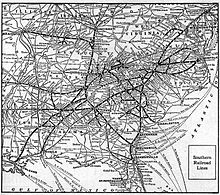

| Locale | Washington, D.C., Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri and Louisiana |

| Dates of operation | 1894–1982 |

| Successor | Norfolk Southern Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The Southern Railway (also known as Southern Railway Company; reporting mark SOU) was a class 1 railroad based in the Southern United States between 1894 and 1982, when it merged with the Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W) to form the Norfolk Southern Railway. The railroad was the product of nearly 150 predecessor lines that were combined, reorganized and recombined beginning in the 1830s, formally becoming the Southern Railway in 1894.[1]

At the end of 1971, the Southern operated 6,026 miles (9,698 km) of railroad, not including its Class I subsidiaries Alabama Great Southern (528 miles or 850 km); Central of Georgia (1729 miles); Savannah & Atlanta (167 miles); Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway (415 miles); Georgia Southern & Florida (454 miles); and twelve Class II subsidiaries. That year, the Southern itself reported 26,111 million net ton-miles of revenue freight and 110 million passenger-miles. Alabama Great Southern reported 3,854 million net ton-miles of revenue freight and 11 million passenger-miles; Central of Georgia 3,595 and 17; Savannah & Atlanta 140 and 0; Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway 4906 and 0.3; and Georgia Southern & Florida 1,431 and 0.3.

The railroad joined forces with the Norfolk and Western Railway in 1980 to form the Norfolk Southern Corporation. The Norfolk Southern Corporation was created in response to the creation of the rival CSX Corporation by a number of railroads in the eastern United States (adopting the name CSX Transportation for its rail system in 1986). Southern and N&W continued as operating companies of Norfolk Southern until in 1982, when Norfolk Southern merged nearly all of N&W's operations into Southern to form the Norfolk Southern Railway. The railroad has used that name since.

History

[edit]Official predecessors

[edit]- Richmond, York River and Chesapeake Railroad (1894)

- Richmond and Danville Railroad (1894)

- Memphis and Charleston Railroad (1894)

- East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railway (1894)

- Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway (1894)

Creation and independent status

[edit]

The pioneering South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, Southern's earliest predecessor line and one of the first railroads in the United States, was chartered on December 19, 1827, and ran the nation's first regularly scheduled steam-powered passenger train – the wood-burning Best Friend of Charleston – over a six-mile section out of Charleston, South Carolina, on December 25, 1830.[2][3] By October 1833, its 136-mile line to Hamburg, South Carolina, was the longest in the world.[2][3] The company leased enslaved African Americans from plantation owners when free white people refused to work in the swamps. The company eventually purchased 89 people to work as slaves.[4]

As railroad fever struck other Southern states, networks gradually spread across the South and even across the Appalachian Mountains. By 1857, the Memphis and Charleston Railroad was completed to link both Charleston, South Carolina, and Memphis, Tennessee.[5] The Western North Carolina Railroad was halted because voters were angry about that law allowed purchasers of private bonds to have the train tracks veer to their towns. The provision of the laws that allowed this was not repealed until Reconstruction.[6]

Rail expansion in the South was also halted with the start of the Civil War. The Battle of Shiloh, the Siege of Corinth and the Second Battle of Corinth in 1862 were motivated by the importance of the Memphis and Charleston line, the only east–west rail link across the Confederacy.[7] The Chickamauga Campaign for Chattanooga, Tennessee, was also motivated by the importance of its rail connections to the Memphis and Charleston and other lines. Also, in 1862, the Richmond and York River Railroad, which operated from the Pamunkey River at West Point, Virginia, to Richmond, Virginia, was a major focus of George McClellan's Peninsular Campaign, which culminated in the Seven Days Battles and devastated the tiny rail link. Late in the war, the Richmond and Danville Railroad was the Confederacy's last link to Richmond, and transported Jefferson Davis and his cabinet to Danville, Virginia, just before the fall of Richmond in April 1865.[8]

Known as the "First Railroad War", the Civil War left the South's railroads and economy devastated. Most of the railroads, however, were repaired, reorganized and operated again. Convict lease was a near continuation of slavery as charges were often only applied to people of African descent. Five-hundred African Americans were assigned to provide back breaking labor on the Western North Carolina Railroad. Men were shipped to and from the worksite in iron shackles and around twenty were drowned in the Tuckasegee River weighted down by their shackles.[6] In the area along the Ohio River and Mississippi River, construction of new railroads continued throughout Reconstruction. The Richmond and Danville System expanded throughout the South during this period, but was overextended, and came upon financial troubles in 1893, when control was lost to financier J. P. Morgan, who reorganized it into the Southern Railway System.

Southern Railway came into existence in 1894 through the combination of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, the Richmond and Danville system and the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad. The company owned two-thirds of the 4,400 miles of line it operated, and the rest was held through leases, operating agreements and stock ownership. Southern also controlled the Alabama Great Southern and the Georgia Southern and Florida, which operated separately, and it had an interest in the Central of Georgia.[1] Additionally, the Southern Railway also agreed to lease the North Carolina Railroad Company, providing a critical connection from Virginia to the rest of the southeast via the Carolinas.[9]

Southern's first president, Samuel Spencer, brought more lines into Southern's organized system.[10] During his 12-year term, the railway built new shops at Spencer, North Carolina, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Atlanta, Georgia, upgraded tracks, and purchased more equipment.[10] He moved the company's service away from an agricultural dependence on tobacco and cotton and centered its efforts on diversifying traffic and industrial development.[10] On November 29, 1906, Spencer was killed in a train wreck.[11]

After the line from Meridian, Mississippi, to New Orleans, Louisiana, was acquired in 1916 under Southern's president Fairfax Harrison, the railroad had assembled the 8,000-mile, 13-state system that lasted for almost half a century.[10] Additionally, Southern have operated 6,791 miles of road at the end of 1925, but its flock of subsidiaries added 1000+ more.

In 1912, the Southern Railway leased most of its Bluemont, Virginia, branch to the newly formed Washington and Old Dominion Railway. In 1945, the Southern sold most of the remnant of the branch to the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, the successor to the Washington and Old Dominion Railway.[12]

The Central of Georgia became part of the system in 1963, and the former Norfolk Southern Railway was acquired in 1974.[10] Despite these small acquisitions, the Southern disdained the merger trend when it swept the railroad industry in the 1960s, choosing to remain a regional carrier. In 1978 President L. Stanley Crane[13][14] said the refusal to add routes through merger was a mistake, especially the decision not to add a connecting route to Chicago.[15]

The Southern tried to gain access to Chicago by targeting the Monon Railroad and the Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad but both those railroads went to Southern's competitor, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.[16] A decade later Crane tried to rectify the situation by merging with the Illinois Central Railroad.[17] When that failed, he petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to give Southern the old Monon routes and the old Atlantic Coast Line route from Jacksonville to Tampa by way of Orlando among other properties as a condition of the I.C.C.'s approval of the Seaboard Coast Line – Chessie System merger in 1979. While the request was supported by the I.C.C.'s Enforcement Bureau, it was ultimately unsuccessful.[18]

Becoming part of the Norfolk Southern Corporation

[edit]In response to the creation of the CSX Corporation in November 1980, the Southern Railway joined forces with the Norfolk and Western Railway and formed the Norfolk Southern Corporation in 1980 which began operations in 1982, further consolidating railroads in the eastern half of the United States.[19][20]

The Southern Railway was renamed Norfolk Southern Railway as the Norfolk and Western Railway became a subsidiary to its system on June 1, 1982.[20][21] The railroad then acquired more than half of Conrail on June 1, 1999.[20]

Notable features

[edit]Southern and its predecessors were responsible for many firsts in the industry. Starting in 1833, its predecessor, the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road, was the first to carry passengers, U.S. troops and mail on steam-powered trains[22] and experimented with railroad lighting. They had a pine log fire on a flatcar, covered in sand, to provide light at night before inexpensive kerosene was invented for lamps.[23]

The Southern operated some of the largest heavy repair shops of any US southeastern railroad. The oldest shops were located in Knoxville, Tennessee, first built in 1855. In 1890 they were relocated to the northwest side of the city and renamed Coster. The 1850s-era Atlanta, Georgia shops were moved to the south side of the city in 1883. These were originally called South Shops but later renamed to Pegram. In 1907 a new terminal with medium repair capabilities was added to the north side of Atlanta. The modern and complete Spencer Shops, located 2.5 miles north of Salisbury, North Carolina, were opened in 1896. Another new shop site was established on the north side of Birmingham, Alabama near the Findley Yard in 1924, taking the place of two obsolete facilities. The Princeton, Indiana shops were built in 1890. After the railroad switched to diesel power, the primary repair shops were consolidated to Spencer and Pegram.[24]

The Southern Railway began dieselization in 1941, and was the largest all-diesel railroad when it retired its last steam locomotive in 1953. The Southern Railway was active in mechanization, used helper engines, is widely credited with inventing unit trains for coal and new freight cars,[25] and understood the power of marketing using the promotional phrase "Southern Gives a Green Light to Innovation".[26]

In 1966, a popular steam locomotive excursion program was instituted under the presidency of W. Graham Claytor Jr., and included Southern veteran locomotives No. 630, No. 722,[27] No. 4501, and Savannah & Atlanta No. 750 along with non-Southern locomotives such as Texas & Pacific No. 610,[28] Canadian Pacific No. 2839,[29] and Chesapeake & Ohio No. 2716.[30] The steam program continued after the 1982 merger with the Norfolk and Western to form the Norfolk Southern, though increased operating costs and concerns ended the program in 1994.[30][31] Norfolk Southern reinstated the steam program on a limited basis from 2011 to 2015, as the 21st Century Steam program.

In the early 2000s, a 22-mile (35 km) loop of former Southern Railway right-of-way encircling central Atlanta neighborhoods was acquired and is now the BeltLine trail.

Passenger trains

[edit]

Along with its famed Crescent and Southerner, the Southern's other named passenger trains included:[32]

- Aiken-Augusta Special

- Airline Belle

- Asheville Special

- Birmingham Special

- Carolina Special

- Fast Mail "Old 97"

- Florida Sunbeam

- Goldenrod

- Kansas City–Florida Special

- Land of the Sky Special

- Memphis Special

- New Yorker

- Peach Queen

- Pelican

- Piedmont Limited

- Ponce de Leon

- Queen and Crescent Limited

- Royal Palm

- Skyland Special

- Sunnyland

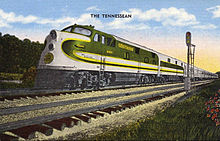

- Tennessean

The Southern Railway also handled ticket sales and operations for subsidiary railroads, such as:

- The Nancy Hanks (operated by Central of Georgia Railway)[33]

- The Man O' War (operated by Central of Georgia Railway)

The Southern Railway also participated in the operation of the City of Miami, which was operated by the Southern Railway over the Central of Georgia trackage from Birmingham, Alabama, to Albany, Georgia, where it traded off with the Seaboard Coast Line until its discontinuation in 1971.

When Amtrak took over most intercity rail service in 1971, Southern initially opted out of turning over its passenger routes to the new organization. However, it shared operation of its flagship train, the New Orleans–New York Southern Crescent, with Amtrak. Under a longstanding haulage agreement inherited from Penn Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad, Amtrak carried the train north of Washington. By the late 1970s, growing revenue losses and equipment-replacement expenses convinced Southern it could not continue in the passenger business. It handed full control of its passenger routes to Amtrak in 1979.

Roads owned by the Southern Railway

[edit]- Alabama Great Southern Railway (AGS)

- Albany and Northern Railway (A&N)

- Atlantic & Eastern Carolina Railway (A&EC)

- Birmingham Terminal Company

- Camp Lejeune Railroad Company

- Carolina and Northwestern Railway (C&NW)

- Central of Georgia Railway (CofG)(CG)

- Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway (CNO&TP)

- Chattanooga Station Company

- Chattanooga Traction Company (CTC)

- Georgia and Florida Railroad (G&F)

- Georgia Ashburn Sylvester and Camilla Railway (GAS&C)

- Georgia Northern Railway (GANO) – acquired in 1967

- Georgia Southern and Florida Railway (GS&F)

- Interstate Railroad (INT)

- Kentucky and Indiana Terminal Railroad (K&IT)

- Sievern and Knoxville Railroad

- Live Oak Perry and Gulf Railway (LOP&G)

- Louisiana Southern Railway (LS)

- New Orleans and North Eastern Railway (NO≠)

- New Orleans Terminal Company (NOTCO)

- Norfolk Southern Railway (NS)

- Savannah & Atlanta Railway (SA)

- Saint John's River Terminal Company (SJRT)

- State University Railroad Company (54%)

- South Carolina and Georgia Railroad (SC&G)

- South Georgia Railway (SG)

- Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia Railway (TA&G)

- Tennessee Railway (TENN)

Major railroad yards

[edit]- Chattanooga, Tennessee – DeButts Yard (formerly Citico Yard)

- Atlanta, Georgia – Inman Yard

- Spencer, North Carolina – Spencer Yard

- Birmingham, Alabama – Norris Yard

- Knoxville, Tennessee – Sevier Yard

- Macon, Georgia – Brosnan Yard[34]

- Sheffield, Alabama – Sheffield Yard

- Alexandria, Virginia – Cameron Yard

Company officers

[edit]Presidents of the Southern Railway:

- Samuel Spencer (1894–1906)[35]

- William Finley (1906–1913)

- Fairfax Harrison (1913–1937)

- Ernest E. Norris (1937–1951)

- Harry A. DeButts (1951–1962)

- D. William Brosnan (1962–1967)

- W. Graham Claytor Jr. (1967–1977)[36]

- L. Stanley Crane[13][14] (1977–1980)

- Harold H. Hall (1980–1982)

Heritage unit

[edit]To mark its 30th anniversary, Norfolk Southern painted 20 new locomotives with the paint schemes of predecessor railroads. GE ES44AC #8099 was painted in Southern Railway's green and white livery.[37][38] As of May of 2023, the engine was released from the Juniata Engine shops[39] in Altoona, Pennsylvania, after having been repaired from a derailment in December 2021.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Southern Railway History". Southern Railway Historical Association. March 5, 2017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Marrs, Aaron W. "South Carolina Railroad: December 19, 1827–1902". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Loy, Hillman & Cates (2004), p. 7.

- ^ Ulrich Bonnell Phillips (1908). Transportation in the Ante-bellum South: An Economic Analysis. Ulrich Bonnell Phillips. pp. 148–153.

- ^ Harper's Encyclopædia of United States History from 458 A.D. to 1905: Based Upon the Plan of Benson John Lossing ... Harper & brothers. 1906. p. 526.

- ^ a b Sue Greenberg; Jan Kahn (1997). Asheville: A Postcard History. Arcadia Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7524-0807-1.

- ^ Cozzens, Peter (1997). The Darkest Days of the War The Battles of Iuka&Corinth. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-8078-5783-0.

- ^ John Stewart (2014). Jefferson Davis's Flight from Richmond: The Calm Morning, Lee's Telegrams, the Evacuation, the Train, the Passengers, the Trip, the Arrival in Danville and the Historians' Frauds. McFarland. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4766-1640-7.

- ^ North Carolina. Board of Railroad Commissioners (1895). Annual Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of North Carolina. J. Daniels, state printer. pp. iv–xiii.

- ^ a b c d e Loy, Hillman & Cates (2004), p. 8.

- ^ "Samuel Spencer Killed In Wreck". The New York Times. November 30, 1906. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ (1) Harwood, Herbert H. Jr. (April 2000). Rails to the Blue Ridge: The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, 1847–1968 (PDF) (3rd ed.). Fairfax Station, Virginia: Northern Virginia Parks Authority. pp. 45–46, 90. ISBN 0-615-11453-9. LCCN 77104382. OCLC 44685168. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2017. In Appendix K of Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority – Pre-filed Direct Testimony of Mr. Hafner, Mr. Mcray and Mr. Simmons, November 30, 2005 (Part 5), Case No. PUE-2005-00018, Virginia State Corporation Commission. Obtained in "Case Docket Search". Virginia State Corporation Commission. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

(2) Williams, Ames W. (1989). The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad. Arlington, Virginia: Arlington Historical Society. p. 94. ISBN 0-926984-00-4. OCLC 20461397. - ^ a b "NAE Website – Mr. L. Stanley Crane". Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ a b L. Stanley Crane (born in Cincinnati, 1915) raised in Washington, lived in McLean before moving to Philadelphia in 1981. He began his career with Southern Railway after graduating from The George Washington University with a chemical engineering degree in 1938. He worked for the railroad, except for a stint from 1959 to 1961 with the Pennsylvania Railroad, until reaching the company's mandatory retirement age in 1980. Crane went to Conrail in 1981 after a distinguished career that had seen him rise to the position of CEO at the Southern Railway. He died of pneumonia on July 15, 2003, at a hospice in Boynton Beach, Florida

- ^ "Deadline Set on Rail Merger" (PDF). U.S.Government Publishing Office. June 30, 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

The purpose of the agency is to give railroads an opportunity to purchase portions of the Chessie and Seaboard systems. Cited as an example was the Southern Railroad's interest in the Louisville & Nashville line between Louisville, Ky., and Chicago, Ill. 'There may be other examples where parties have been unable to agree on specific terms such as price of properties and operational arrangements because of a failure to communicate adequately,' the agency said.

- ^ "Monon, L&N. Roads Act to Merge". Chicago Tribune. March 22, 1968. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ "Southern Dreams of Chicago". Chicago Tribune. July 5, 1978. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ April 8, 1978 "I.C.C. Urged to Split Seaboard Coast Line". The New York Times. April 8, 1978. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ "Southern Rail, N&". The Washington Post. February 22, 1982. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Norfolk Southern merger family tree". Trains. June 2, 2006. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Davis (1985), p. 165.

- ^ Brown, William H. (1871). "Chapter XXIX: Explosion of "Best Friend"". The History of the First Locomotives in America; From Original Documents And The Testimony Of Living Witnesses. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Archived from the original on November 26, 2001. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Christian Wolmar (March 2, 2010). Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World. PublicAffairs. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-58648-851-2. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Starr 2024.

- ^ Brian Solomon; Patrick Yough (July 15, 2009). Coal Trains: The History of Railroading and Coal in the United States. MBI Publishing Company. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-61673-137-3. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Kelly, John (April 5, 2001). "Selling the service: A look at memorable railroad slogans and heralds through the years". Classic Trains Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Loy, Hillman & Cates (2004), p. 124.

- ^ Loy, Hillman & Cates (2005), p. 114.

- ^ Loy, Hillman & Cates (2005), p. 123.

- ^ a b Schafer (2000), p. 134.

- ^ Phillips, Don (October 29, 1994). "Norfolk Southern plans to end nostalgic steam locomotive program". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Schafer (2000), pp. 127–132.

- ^ Loy, Hillman & Cates (2004), p. 93.

- ^ Loy, Hillman & Cates (2004), p. 54.

- ^ "The History of the railroad and Spencer". North Carolina Transportation Museum. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ quotes from article by journalist Don Phillips of the Washington Post in a "Tribute to W. Graham Claytor, Jr." published May, 1994

- ^ Heritage Locomotives Archived February 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Norfolk Southern

- ^ Norfolk Southern Heritage Locomotives Archived December 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Norfolk Southern

- ^ "AltoonaWorks.info". www.altoonaworks.info. Archived from the original on June 16, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ "NS derailment damages Southern Railway heritage unit". Trains. December 14, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Davis, Burke (1985). The Southern Railway: Roads of the Innovators (1st ed.). University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1636-1.

- Loy, Sallie; Hillman, Dick; Cates, C. Pat (2004). The Southern Railway. Images of Rail (1st ed.). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-1641-7.

- Loy, Sallie; Hillman, Dick; Cates, C. Pat (2005). The Southern Railway: Further Recollections. Images of Rail (1st ed.). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-1831-2.

- Schafer, Mike (2000). More Classic American Railroads (1st ed.). Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-7603-0758-X.

- Starr, Timothy (2024). The Back Shop Illustrated, Volume 3: Southeast and Western Regions. Privately printed.

Further reading

[edit]- The Historical Guide to North American Railroads, Third Edition (3rd ed.). Kalmbach Publishing. 2014. pp. 273–275. ISBN 978-0-89024-970-3.

- Harrison, Fairfax. A History of the Legal Development of the Railroad System of Southern Railway Company. Washington, D.C.: 1901.

- Murray, Tom (2007). Southern Railway. MBI Railroad Color History (1st ed.). Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2545-2.

- Prince, Richard E. (1970). Steam Locomotives and Boats: Southern Railway System (2nd ed.). Wheelwright Lithographing Company. ISBN 0-9600088-4-5.

External links

[edit]- Southern Railway Historical Association covers Southern Railway history

- Railroad lines abandoned by the Southern Railway at the Wayback Machine (archived 2008-05-11), which was replaced by a map version on AbandonedRails.com.

- Southern Railway (U.S.)

- Defunct Alabama railroads

- Defunct Florida railroads

- Defunct Georgia (U.S. state) railroads

- Defunct Illinois railroads

- Defunct Indiana railroads

- Defunct Kentucky railroads

- Defunct Mississippi railroads

- Defunct Missouri railroads

- Defunct North Carolina railroads

- Defunct South Carolina railroads

- Defunct Tennessee railroads

- Defunct Virginia railroads

- Defunct Washington, D.C., railroads

- Former Class I railroads in the United States

- Predecessors of the Norfolk Southern Railway

- Railway companies established in 1894

- Railway companies disestablished in 1990

- Standard gauge railways in the United States